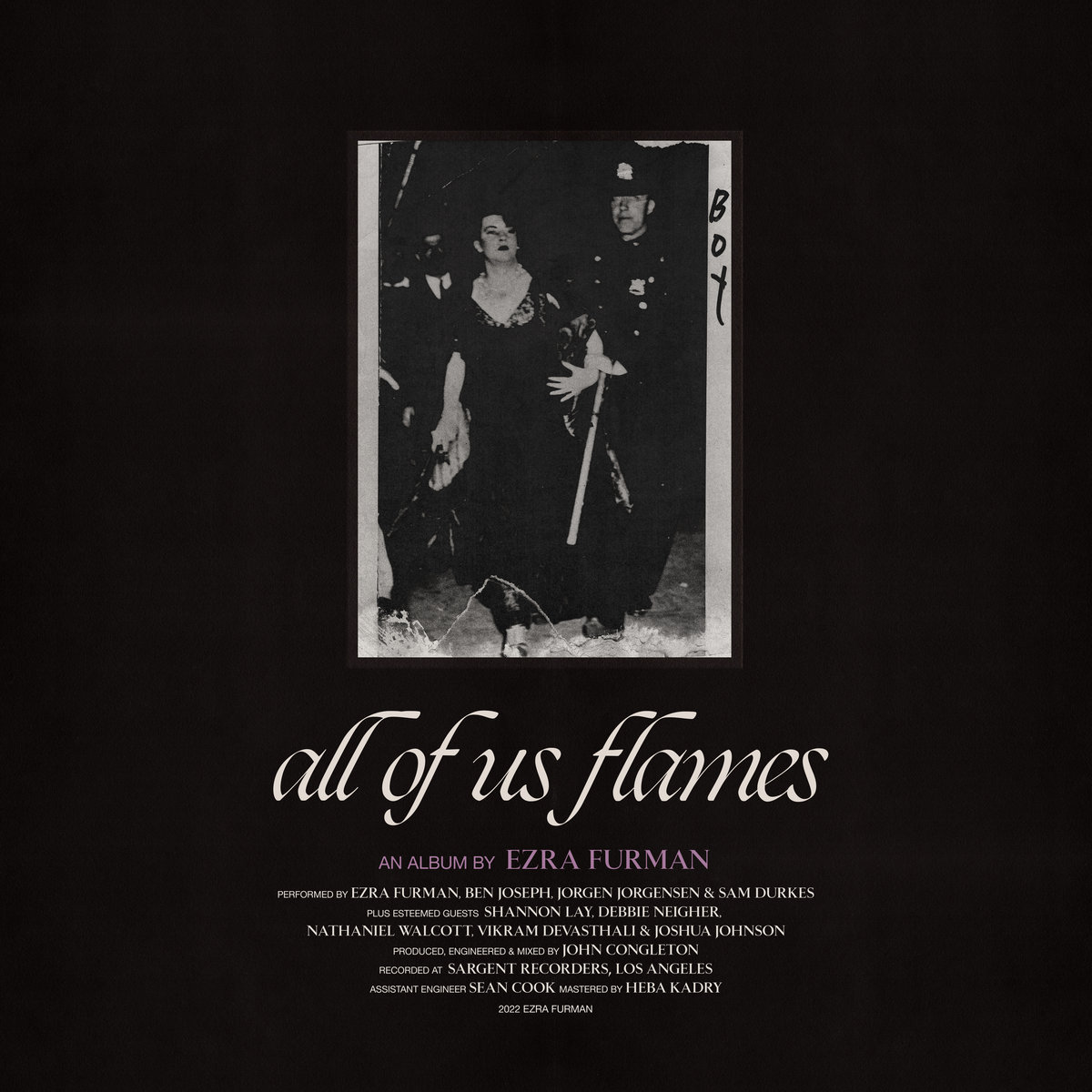

Album Review: Ezra Furman – All Of Us Flames

[Bella Union; 2022]

Discussing the impact of context on the reception of music is a frustrating debate. Art cannot be separated from an artist, as it is directly correlated to the identity of the creator – conscious and unconscious. But once published, the artwork also exists outside of the artist’s reach and becomes part of the audience’s own biography and experiences. Even though the past few decades have seen fairly detailed creator information revealed, there are plenty of artists shrouded in mystery or mystique – furthermore, it seems most members of the public are more keen on consuming art than to ponder one’s inner machinations. “We must talk about the artist” is therefore as much a blessing as a curse, for some more than for others.

In the case of Ezra Furman, this split is more present than for many others. Leaving The Harpoons in the early 2010s, Furman released a string of indie pop solo albums that were moderately successful but mostly considered overtly polished. The Chicago musician has been declared a mad hipster in the same vein of Brooklyn fashion that emerged during the heyday of the blog – it didn’t help that there were some pretty obvious parallels to bigger and bigger contemporaries. most notable in composition and sound, such as Amanda Palmer and Bradford Cox.

But, as its production grew, so did Furman. Where 2015 People with perpetual motion still ran in the vein of Atlas Sound’s obsession with the 50s and 60s, 2018 Transangelic Exodus leaned more towards a heavy Velvet Underground and Lou Reed palette. Still, Furman couldn’t shake the “ordinary” taste until 2019 was pretty good twelve nudes reframed his songwriting into a raucous layer of nocturnal, modernist punk, making his own Monomania. Well, it’s got a little less bite, but it was a huge step forward for Furman, promising an exciting maturity lacking in previous work, which could mark a bright future.

We all Flames follows Furman’s greatest professional achievement, marking the show Sex education, and from the beginning of the album, it is obvious that the musician took one step forward and two steps back. Inspired by the aura of great American rock songwriters, it’s rich in references to early Springsteen and the overtly Christian tunes of Bob Dylan’s 80s albums – which means it’s also much more formal and tailored. than its predecessor.

A bit like Saint Vincent daddy’s house, his ideas of pop classicism as an opportunity to express a queer experience are ultimately wrapped up in the conservative medium of highway pop radio. There is very little beauty here, and even fewer surprises. That means the exceptions, like John Lennon’s wonderfully tinged “Point Me To Reality,” stand out even more, communicating an urgency of nostalgia that carries over via its chorus. The prominent drop of “motherfucker” is speculative, but it works because it’s embedded in an unassuming structure and calls to mind the rebellious crooked side of big rock gods eager to provoke moral watchdogs. In other places, Furman uses a disintegrating effect, similar to an old record or ramshackle tape: the modest “Ally Sheedy in the Breakfast Club” is saved by this.

But these positives can’t hide that some of these songs are eerily similar in tone and structure – either to each other or referencing classics. “Poor Girl A Long Way From Home” recycles Enya’s “Sail Away” in its chorus, while “Dressed in Black” picks up the opener from, well, The Shangri-Las’ “Dressed in Black.” It’s hokey in a way where it feels more overt than charming. In general, the formula Furman relies on does his strengths a disservice – the classic Springsteen writing style present in “Forever in Sunset” and “Lilac and Black” feels limited and part of something. other more than her own.

And this is where the gaze turns outward and asks questions related to identity and experience. Furman’s lyrics have often dealt with gender identity and queer sexuality in a stark and unvarnished way, putting things straight and with naked honesty. However, here she falls into the trappings of cliché, reusing images that seem – once again – not just recycled but tired. “I saw the truth undress” approaches a “pale emperor” image in a way that leaves little to the imagination but also abandons the power of words, simply describing a singular image until it is quite worn. “Book of Our Names” again focuses on a single image – that there is a story somehow untold in queer culture – but only finds gray slogans without much color: “And our names will be heard at through prison walls / Through damp city streets and roll calls / And we’ll read it till this whole empire falls / And then we’ll read it on”. There’s an air of a protest song here, but it just feels anonymous and formless in its prosaic approach. It’s as if, in a quest to say it all out loud, Furman forgets that it’s the unsaid, the barely mentioned, that resonate in our hearts. Poetry is a secret language that makes expression beyond the meaning of words.

So all this train and travel stories do indeed hark back to some of Dylan’s work from the 80s, but the problem to be solved is that a lot of that material was already wrapped in tired imagery, which meant more small chapters of a larger than individual book. pages. Dylan wasn’t as lost in that decade as people assume. He simply searched for new forms of expressions related to his interest in Christian symbolism, then related them to his familiar interest in American folklore. So when Furman does this, not only is she imagining what could be called a non-existent past, but she is adapting to a mode that her own artistic endeavors cannot respond to. It’s all the style, minus the substance that made this style.

This is also interesting in a more ontological context. It can be observed that a modern canon of music is being built where members of the trans community work both inside and outside the constraints of the “music business”, shaping an identity musical of their own and which consciously plays with history. Adopting pop formulas while inverting them simultaneously, works like Cats Millionaire fun fun funby Patricia Taxxon buzzerby Cindy Lee What is tonight for eternity and Sophie’s The oil of all pearl interiors find a colorful sonic representation of collapsing borders and coalescing contradictions. Meanwhile, artists like Uboa, Sewerslvt and Backxwash consciously choose confrontation and noise to express pain and express the absurdity of dichotomies. These albums feel like dreams, and sometimes even nightmares, but they blur all notions of what the genre should or should be, and what it always has been. These examples are not meant to be a direct comparison of these artists to Furman’s music, but it is somewhat odd how his music stays on the preconceived paths inherent in his influences more than questioning those same legacies.

There’s not really any tension in We all Flames, no burning anger, no heated debate. “Dressed in Black”, which would allow for a direct engagement with the past, even feels like consciously playing with the idea of an illusion disguised as love: “Baby, I know our time will come, we’ll run away / When get us back the money saved / We’ll run away to the sun / Store supplies, my knives, your gun / You’ll call my name and I’ll come”. decidedly too polite.Compare that with the crushing soul pain of Xiu Xiu’s cover of “Fast Car”, which is also built on a song from the past but expresses the desire and knowledge of despair in a more muted way. , but incredibly touching Furman’s potential only suggests that it never explodes, never fully forms – it always exists in the very lines painted in front of her.

What’s left is a record that feels overly polished, neatly executed and often poorly thought out. Music for nodding and toe tapping, then turn it off and keep going. Once the train leaves the station, there’s not much left after the nostalgia for the past that Furman alludes to. twelve nudes showcased inherent power and talent; we can only aspire to a better future than this present.